Leading the Witness & The Power of Prompts

A deep dive into how the infamous leading the witness dilemma ties into conquering our own biases.

5 min read

Mitchell Pousson II / August 20, 2020

They help comprise the way we interact with one another, how we approach our work, and ultimately shape the thoughts and opinions we hold dearest.

Before we continue looking into just how powerful prompts are, it may be helpful to check out the official definition.

Prompt (verb) 1: to move to action : INCITE

2: to assist (one acting or reciting) by suggesting or saying the next words of something forgotten or imperfectly learned : CUE

3: to serve as the inciting cause of

We see these examples of prompting in the workplace, at home, and even in our social lives.

But there's one example that really sums up just how powerful prompting can be: the classic leading the witness dilemma.

Lawyers worldwide actively deploy this tactic in order to extract from the witness the information they are after.

The 4 main types include:

- Suggestive Insinuation (Ex. "Did you see Tom at 5 PM?")

- Too Many Variables (Ex. "Did Haley hit you in the face, with her fist?")

- Glossing Over Details (Ex. "Mr. Smith owned this revolver, correct?" followed by “And this is the same revolver that was found at the murder scene, correct?")

- Asserting Unconfirmed Qualities (Ex. "You told John that his order would be completed by Tuesday, didn't you?")

If you are familiar with the rule of law, then you know these tactics are strictly prohibited in the U.S. as well as many other countries all over the globe.

The reason why?

They interfere with the witness's duty to accurately recall the facts while also hindering the jury's ability to reach a well-informed and unbiased verdict.

So what do these examples have to do with human cognition and behavior?

More than you think.

How we process information and form opinions has just as much to do with the manner in which the material is presented in as the material itself.

The jury's perception, the witness's responses, and in the most extreme cases—even the witness's own thoughts and memories are all influenced by the lawyer's prompting.

One of the more intriguing aspects of our leading the witness example is how it serves as a perfect analogy for the biases we face when creating a new software product.

In a workshop setting, product managers often use wireframe design templates to help gather early requirements from the team they are working with.

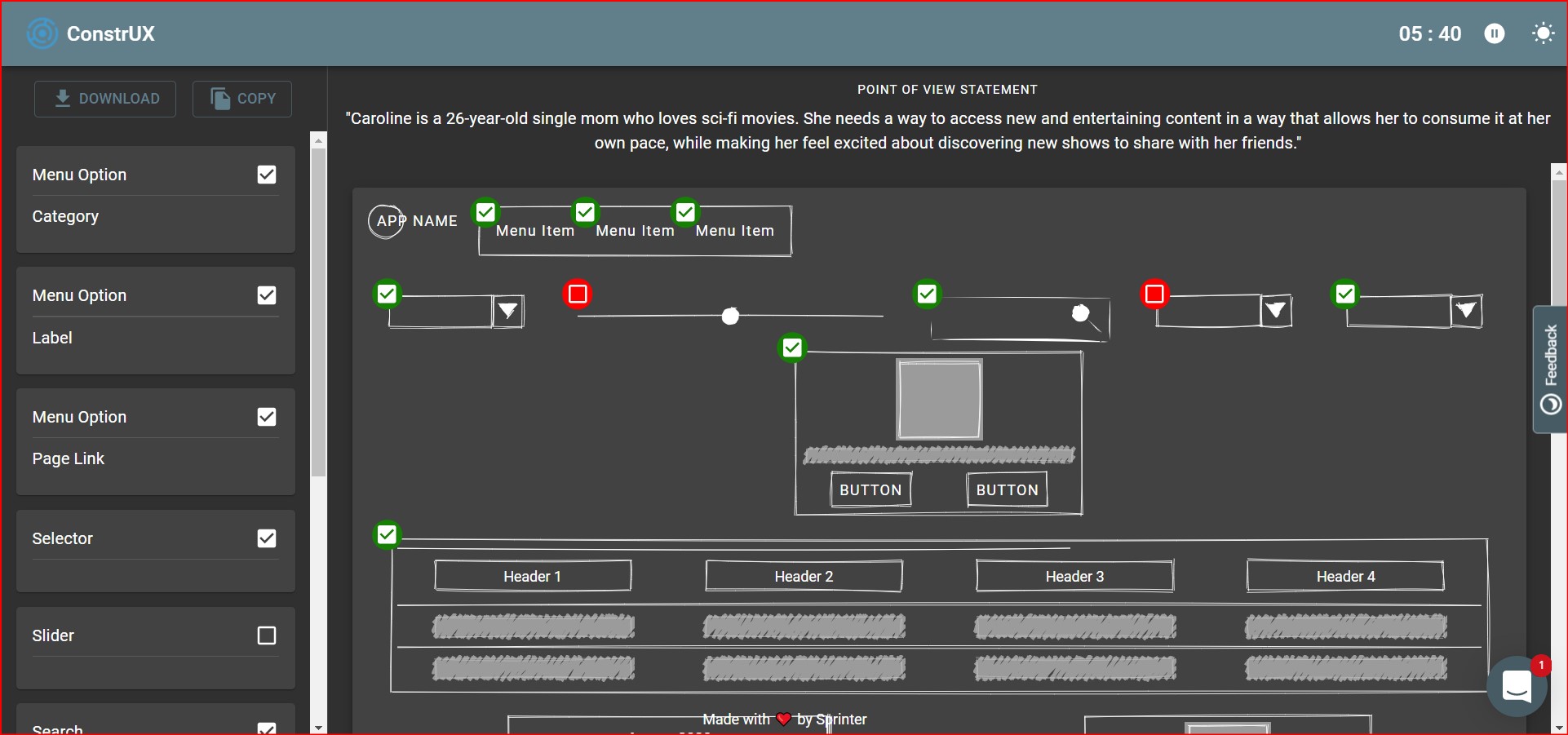

ConstrUX—the product gathering tool we are launching—compiles various wireframe design templates into one easy-to-use ideation exercise.

If we pretend the jury is the product team, and we acknowledge the inevitability of the witness (ConstrUX users) being influenced by the opinionated prompts in a heavily biased environment, then how do we combat this?

Like any good scientist knows, the truth is found in what is repeatable.

In a hypothetical world where justice always prevails—collecting data through multiple witness testimonies in various environments—would help ensure that all of the key information surfaces.

A perfectly rational jury (product team) could then be provided with all of the facts and review the data to find the truth in the midst of all the misleading noise.

The end user's first glimpse of the wireframe is similar to the witness's initial response to the lawyer's prompting—biased by the situation and emotional first takes.

How?

Because the design influences their perception of what functionality is needed the same way the witness responds based on what questions are asked.

The information gained from the witness testimony is similar to the requirements gathered from ConstrUX.

How?

Because the facts from the witness's story can surface independent of the conflating factors so often present in the courtroom (workshop) setting—such as the content, tone of questioning, and the many other agents that tend to bias a jury (product team).

So whether it's in a courtroom or remote product workshop—prompts are powerful, effective, and vital to formulating fresh perspectives and new ideas. But care is needed to optimize their potential in order to extract the information without allowing them to have an outsized impact, so that the best ideas can emerge unscathed.

This is how we help ordinary people build extraordinary products.